By Azaria Kilimba

You could say my career in conservation began with a single elephant. It was 2010, and I was studying for a degree in tourism management, but fieldwork took me to southeastern Tanzania, where I assisted a WWF project to tackle human-elephant conflicts in the villages of the Kilwa region.

Growing up in Tanzania’s cool, rainy and evergreen southern highlands, I had always loved wildlife: my favorite pastime was sketching and painting nature. In Kilwa I discovered a region of fecund coastal forests supporting some of Africa’s most inspiring megafauna: I will never forget the leopard that loomed in the headlights on my very first visit to the field. Biodiversity immediately felt very real to me.

Almost my first task was to investigate what happened to an elephant that WWF had tagged with an electronic collar – the readings showed no movement for quite a while. We never found her body, but I thought long and hard about her fate. It brought home the impacts of environmental degradation here, and why it’s crucial we turn the tide.

Ten years on I help to run WWF’s forest restoration programs across the country. The situation is dire: Tanzania is estimated to be losing around 1,800 square kilometers of its tree cover annually. The common thread in my work is community empowerment. I am from farming roots, so I can relate to the pressures facing people in these remote places just to feed their children. Families scrape out a living from subsistence farming, and as the population grows, slash-and-burn agriculture has become one of the major threats to our ecosystems.

I began in 2012 with a small pilot scheme in the village of Nanjirinji. Our model starts by working with local communities to set aside a portion of their ancestral land as a forest reserve, and in return we help them farm a smaller percentage more commercially. We provide equipment and training on improving farming practices, soil quality and sustainable harvesting practices – hardwood timber is usually the main forest product from the majority of community reserves, which means villagers can take more control over their futures. Benefit-sharing is also critical. We enshrine a system where the profits are split three ways – some for development schemes to lift communities out of poverty, some for technical support, and some to invest back into forest conservation.

I remember a lot of skepticism at first, though. Local people didn’t really believe our proposition would work. So when the first timber yield deposited 32 million Tanzanian shillings (USD 13,750) in the Nanjirinji bank account, elders left it languishing there for three months, as they couldn’t quite process the fact it was their money. It was only when they complained to us about inadequate water supply in the village that we said: ‘This is your forest guys, your earnings. Spend it on what you need!’

Today Nanjirinji has a new primary school, a new market and proper running water. It has become famous countrywide as a grassroots conservation success story. This means we’ve been able to scale up: WWF now has 48 villages operating a similar model, and that has enabled us to move 520,000 hectares of threatened forest into protected status.

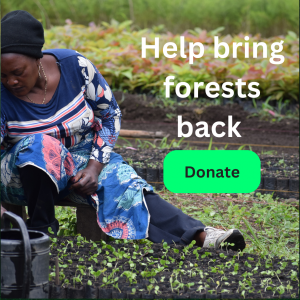

For me, one especially satisfying example is our three-year project to safeguard the Uchungwa Forest, near Mchakama. It is pristine and beautiful – home to seven red-listed animals, from lions, wild dogs and chequered elephant shrews to the southern banded snake eagle – but it was being menaced by poachers and fragmented by illegal logging. This time, the ecological impetus for WWF was a vanishingly rare tree, Erythrina schliebenii. In the old times erythrina was a lifesaver for local people – they used its spiny bark to cure children of fever – but by 2008 it was gone, declared extinct by the IUCN. Our surveys found 50 surviving specimens in southeast Tanzania, including the Uchungwa Forest, and in 2016 we set about engaging villagers to collect their seeds and propagate it in a new tree nursery.

The work was challenging: it’s a muddy five-hour trek to the forest in the planting season, and we quickly discovered that baboons took a liking to the Erythrina tubers, so we had to institute patrols to chase them off. Baboons are curious about anything that humans get up to, in my experience! The breakthrough came when Mchakama’s villagers suggested smearing sifa, a very stinky and oily material made from fish carcasses, traditionally used as a sealant in boatbuilding, on the seedlings to deter them. It worked – a great example of local knowledge aiding an ecological endeavor.

Since then, we have returned almost 30,000 Erythrina saplings to the forest, effectively bringing a species back from the brink of extinction, as well as restoring thousands of other native trees from the village nursery, which also grows orchard varieties to enrich Mchakama’s farmlands, and teak to restock abandoned farm plots. Along with seed-gathering, nurturing, planting and patrolling, the 129 men and 71 women who’ve taken part also carry out wildlife counts, and after five short years, the transformation is palpable. Forest reinvigorates quickly here: on every visit now we find elephant tracks, buffalo dung, where before there was none. Our camera-traps are alive with leopards and porcupines as wildlife returns in numbers.

Off the back of the work in Kilwa, we are now developing a nationwide forest restoration strategy with the Tanzanian government. Together we think we can deliver its pledge to restore 5.2 million hectares of forest by 2030 as part of the AFR100 initiative. Alongside this, we’re running a program called ‘Foresters of the Future’ that involves local children in our restoration work, helping to teach and inspire the next generation of conservationists.

For me personally, though, what gladdens my heart is being able to join hands with people struggling with precarious livelihoods and win them over to the value of conservation. Once it’s explained to them, they understand completely the importance of combating climate change, for example. They experience its effects first-hand, whereas for politicians and company presidents, it is too often merely theoretical. By getting our stories out into the world, I believe we can achieve something big.

This article was originally published in Landscape News as part of a narrative series from global conservationists working as part of Trillion Trees.